Back from Boskone

An Introduction

Calling Boskone my ‘first convention’ is nearly correct. It depends largely on how one defines ‘convention.’ I’ve been to a couple of other cons (Phauxcon, for instance) but this was the first time I attended something this large, and the first time I was a panelist.

Let’s say it was my first big con, then, about which I have many things to say.

I’m not going to break down how the whole weekend went, because I think you have a life you’d like to get back to. Instead, below are a few stray thoughts, both about and inspired by the weekend. This is from the approach of someone attending as an author looking to pick up information about the industry, rather than as a fan of said industry. I am a fan of sci-fi, fantasy and horror stories, and if you are as well I promise you’ll enjoy Boskone just fine. I’m just not concentrating on that aspect so much today.

Authors: different kinds

Here are two sentences I’ve said—each with utter conviction—at different points in my writing career:

“Why would anyone self-publish, if they didn’t have to?”

and

“I don’t know why anyone would sign a contract with a traditional publisher in this market.”

My biggest regret is that I didn’t start taking the sentiment in the latter sentence seriously earlier. At the same time, had I gotten a deal from a publisher back in the mid-2000’s (when I had an agent trying to sell Immortal) I might still be repeating the first sentence.

I was expecting to hear versions of both of these (but mostly the first one) over the weekend, and I didn’t. What I got instead was an appreciation that these are both reasonable approaches to publishing. I heard from aspiring authors who hadn’t considered indie-publishing a viable alternative before speaking with me (which was nice) and from long-established authors looking at indie for their backlist, and wondering how to do that. Everyone was curious, and excited about the possibilities. If there were any traditional publishing zealots out there, they didn’t talk to me.

(Side note: I maintain that the very best way to succeed as a new author of genre fiction, in this marketplace, is to self-publish. I guess this makes me a zealot, but I didn’t say this to anyone.)

There were dragons

The art show was tremendous. Especially these guys.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bt7RvJfgIQc/

Meeting important people

I’ve met Christopher Golden before. I was introduced to him, last year, at a different event. We’ve exchanged emails. He was the Special Guest at Boskone this year, and was always around. He is eminently approachable. Here is how my weekend went.

Christopher Golden: *exists*

Me: Oh, hey, there’s Christopher Golden. I should go say hello.

Me: *does not do this*

This went on the entire weekend. I really don’t know what’s wrong with me.

How to talk about self-publishing without insulting anybody

I was on a panel called The Life Cycle of a Book, whose premise was, and I’m quoting: “it’s not as simple as, ‘the author writes it, then the publisher prints it.’” Since I’m both the author and the publisher for all but one of my books, it kind of is that simple. (All right, not really: I need a cover designer, and when it’s time for audio, I need a narrator. But almost.)

I didn’t want to say that. I also didn’t want to come right out with what I said above, about how going indie is the only sensible thing to do when starting out in genre fiction.

I had a few reasons for not wanting to do this:

- it would likely be rejected as overtly fanatical;

- it was my second panel ever, and I didn’t want to get into an argument on my second panel ever;

- it would have been rude to both the traditionally published authors and the agent with whom I was sharing the panel.

I settled on language that I hope made everyone happy, which was this:

- figure out all the steps needed to publish a book;

- figure out which of those steps you absolutely cannot do yourself;

- get someone else to do those steps for you.

It works because we all have our own definition of ‘publish a book’. If for you it means getting your book into brick-and-mortar bookstores nationwide, you might need a traditional publisher, and to do that, you might need an agent. If your definition is less concerned with brick-and-mortar and more with just getting a book in front of readers, you can skip the agent-and-publisher part, because they are no longer ‘steps needed to publish a book’.

Things I said that caused turmoil

“I don’t use any beta readers, and I edit all my own books.”

As soon as I said this, I told everyone in the audience they definitely needed an editor. I wasn’t going to die on this hill.

“I’m not sure I know what an anti-hero is.”

This was on a panel about villains, and the context was a comparison of the difference between an antagonist and an anti-hero. I was speaking mostly about writing one, because I don’t think my approach to writing an anti-hero differs from writing a hero. (A lot of people have called Adam an anti-hero, for instance.) I just wanted clarification on the terms we were using. Someone in the audience gasped audibly when I said this.

“I make half of my income from audio.”

The gasping, for this one, came from the other people on the panel. I then had to say, again, that my career is not normal, and nobody in the audience should use me as an exemplar.

“Zombie apocalypse stories are hopeful, because the implication is that the reader will survive the apocalypse, because the main character does.”

This was on The Hopeful Future of Science Fiction, and to be honest, it wasn’t that controversial; I was just really proud of the point.

The real villains

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bt8j21kAHGe/

A conversation about Young Adult books

I attended a panel discussion (as an audience member) called When YA Characters Grow Up, which was about the challenges of writing for a character who ages out of the Young Adult category.

I’m facing this problem right now, sort of.

If you skim the reviews for The Spaceship Next Door, you’ll find a few that begin with something along the lines of, ‘well, this is a YA book, but…’ and they say that because Annie Collins is sixteen.

This always bothered me a little. I don’t think it’s a YA book, I didn’t write it to be one, and it seems superficial to argue that a sixteen-year-old protagonist is, by itself, enough to put a book into that category. It’s also absolutely true that I took out the swear words before publishing it, and when HMH acquired the rights I told them they could market it as a cross-appeal YA book. I can cling to both of these possibly contradictory ideas because I don’t think of Young Adult as a genre; I think of it as a demographic.

Anyway. In The Spaceship Next Door, Annie is sixteen. In the sequel, The Frequency of Aliens, Annie is nineteen. It stands to reason that unless I introduce time-travel, Annie Collins is going to be in her twenties the next time I write about her.

The panel focused mostly on why it’s a problem in the first place, because there aren’t a lot of solutions to be found. So I got to thinking about how I might be able to get away with it, and also why I thought my books weren’t actually YA in the first place.

What I arrived at was a more targeted definition of Young Adult. Here, try it on:

YA books are books where the protagonist is a young adult AND where there are no adult Point-of-View (POV) characters.

I thought this was pretty good. It gives me an out to keep aging Annie through as many books as I want to write for her, and a definition to show to anyone who insists what I’ve already written is YA.

I asked the panel:

“Would a solution to the problem of YA characters growing up be mitigated by having adult POV characters in the book?”

The answer (from a successful traditionally published YA author):

“Yes, but a publisher won’t let you do that. They’ll make you take out the adult POV.”

I got two things from this answer:

- I’m on to something. If a publisher would edit out an adult POV before selling a book as YA, it’s reasonable to conclude that adult POV takes the book out of YA.

- If I had tried to sell The Spaceship Next Door before self-publishing, it would have been a fight. Annie’s POV is less than half the book, and the rest is either non-YA POV or omniscient third. I can’t think of a better way to ruin Spaceship with good intentions than by changing this.

There’s actually a third point to be gleaned here, which is that the default for a lot of people is still, ‘but what would a publisher think?’ even on a Boskone panel. I don’t know how long it will be before that stops being the case, if ever.

Miscellany

- If you’re going to make an Open Table dinner reservation a month in advance at the only restaurant on the hotel premises, make sure that restaurant doesn’t have other locations that would be more than happy to take your reservation instead.

- If you’re staying at the hotel, anticipate that it’s going to take more than ten minutes to get to a panel from the room, especially if it’s morning and an elevator is involved.

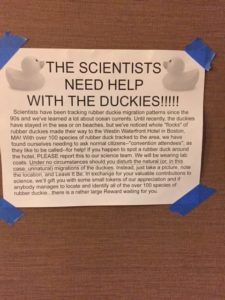

- Plan for ducks

Finally, a big thanks to everyone involved with Boskone. I had a blast. See you all next year!

Join my mailing list for announcements of new blog posts like this one, and to receive my newsletter Writing from the border of Sorrow Falls. You can sign up from here.